20 What is replication?

Replication is the repetition of an experiment under the same or similar conditions to enable better estimation of the effect of interest.

Replication is important because it can increase confidence in a reported effect or phenomenon. An experiment will always have variability by chance. Replication allows us to understand whether chance played a role in the initial experiment. It also allows a degree of control for bias or contextual factors that may have emerged in other experimental settings.

Replication is distinct from reproducibility, which is a re-analysis of the same experimental data by a new analyst.

Reproducibility is an important concept, as even with the same data, people can come to different conclusions about the hypotheses. They can transform the data in different ways. They can use different tests. There are many possible analytic approaches. The result is that experimental data does not in itself provide a conclusion.

Reproducible research is research that provides the full materials required to reproduce a result. It includes features such as the code and data that was used and details on the computational environment in which it was examined. Absent reproducible research, it is not clear what choices were made and the effect of those choices on the conclusion cannot be examined.

In the presence of good reproducible research practices, reproducibility is trivial.

The labels reproducibility and replication are sometimes used interchangeably. Their precise names don’t matter, but the two distinct concepts do.

20.1 Example

Take a look at the following example.

20.1.1 The original paper

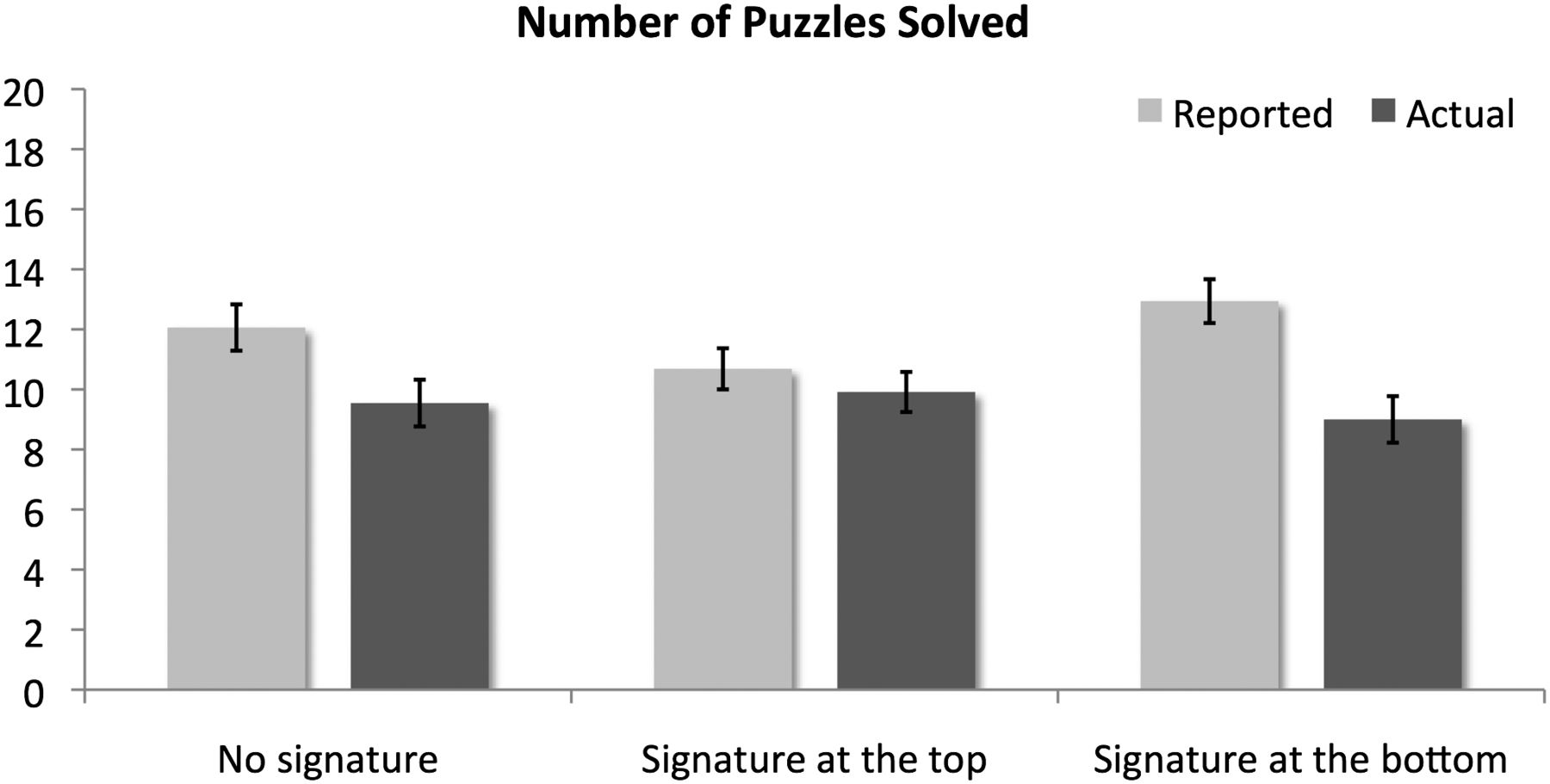

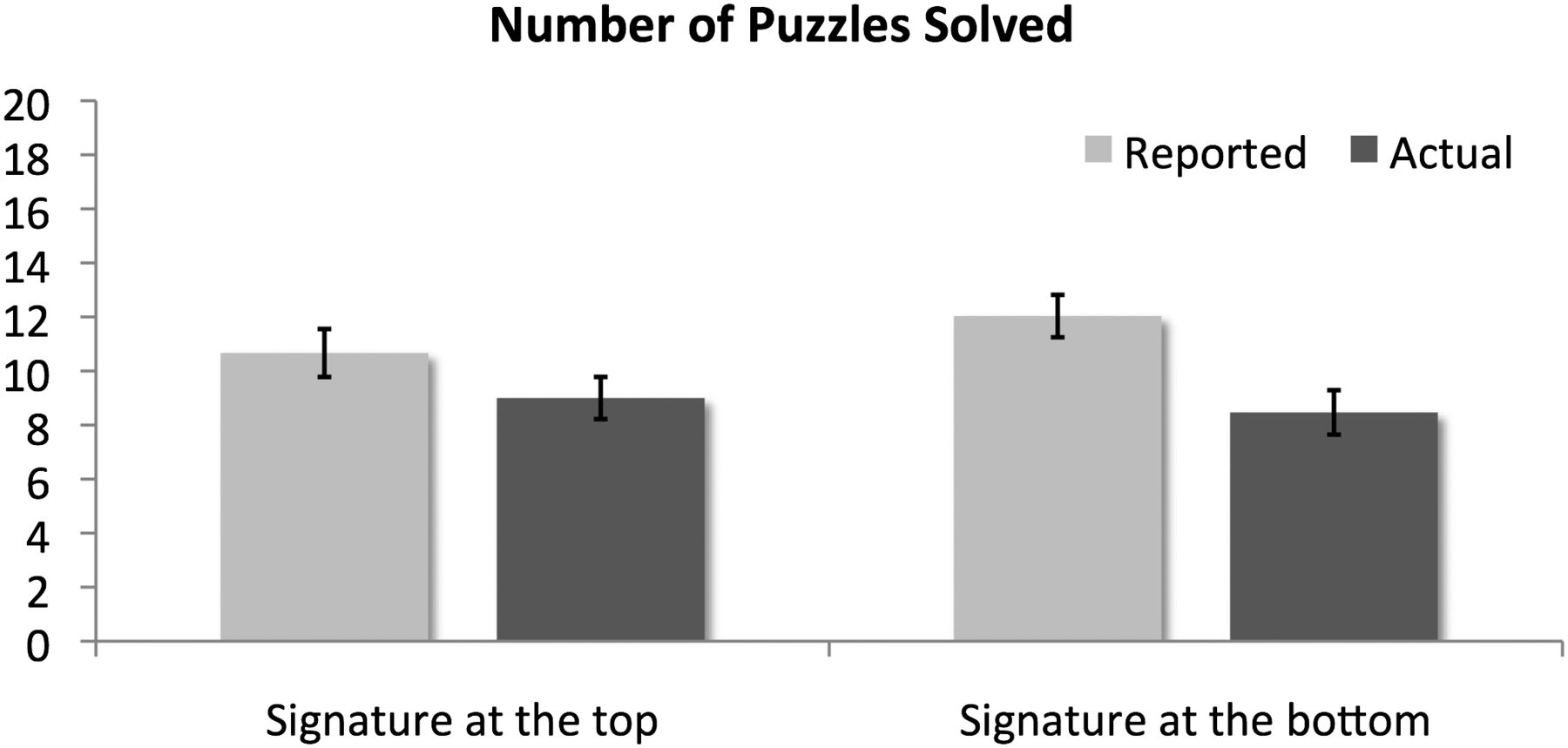

In 2012, Lisa Shu and colleagues (2012) published a paper in PNAS in which they reported that “signing before—rather than after—the opportunity to cheat makes ethics salient when they are needed most and significantly reduces dishonesty.” The paper reported the results of two lab experiments and one field experiment, all suggesting an effect. The following two figures show the experimental results, whereby experimental subjects were asked to report how many problems they had solved.

20.1.2 The replication

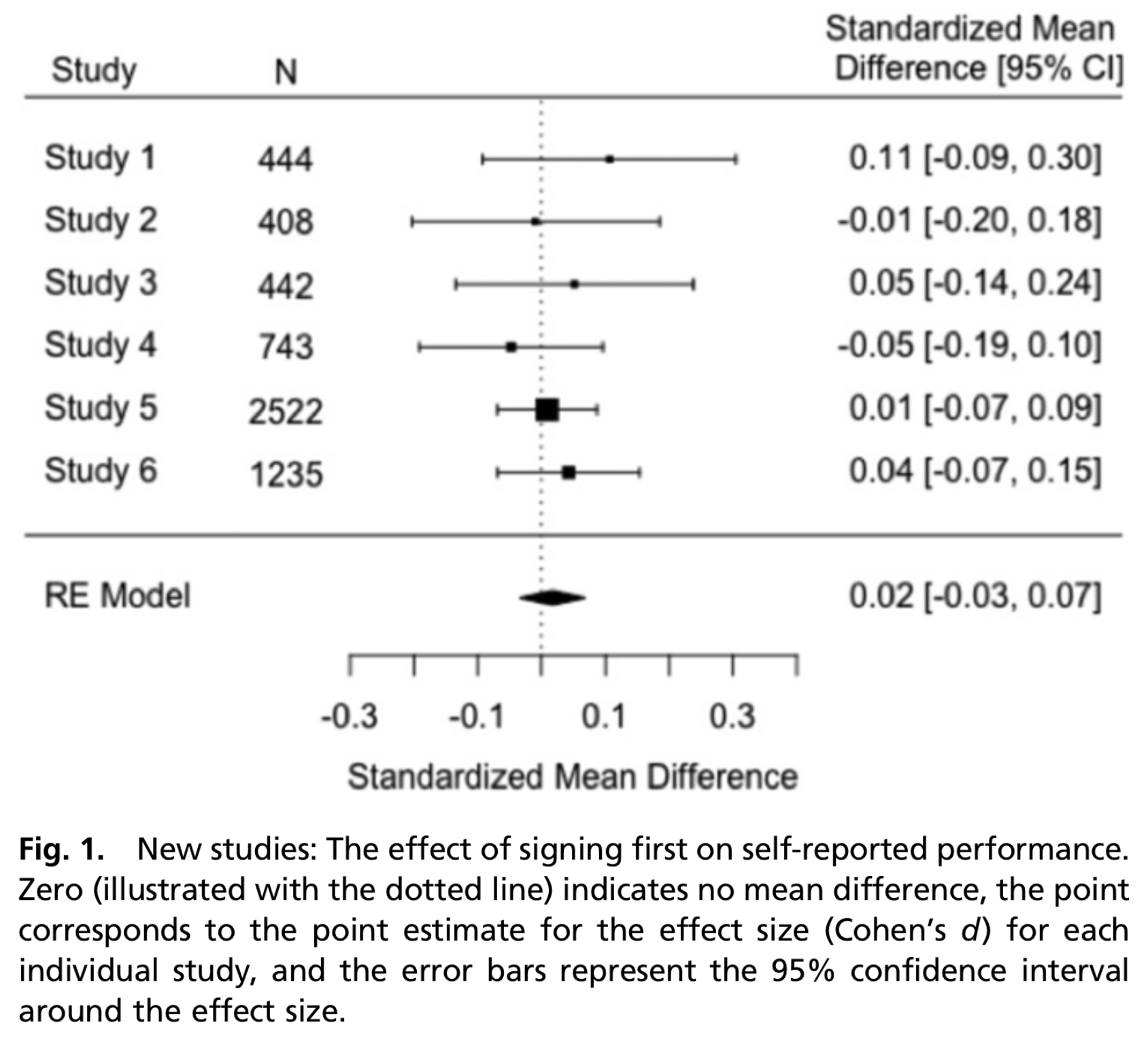

In 2020, a new paper was published in PNAS by Ariella Kristal, Ashley Whillans and the authors of the 2012 paper (Kristal et al., 2020). The abstract reads:

In 2012, five of the current authors published a paper in PNAS showing that people are more honest when they are asked to sign a veracity statement at the beginning instead of at the end of a tax or insurance audit form. In a recent investigation, across five related experiments we failed to find an effect of signing at the beginning on dishonesty. Following up on these studies, we conducted one preregistered, high-powered direct replication of experiment 1 of the PNAS paper, in which we failed to replicate the original result. The current paper updates the scientific record by showing that signing at the beginning is unlikely to be a simple solution for increasing honest reporting.

The results of the replication are shown in the following figure.

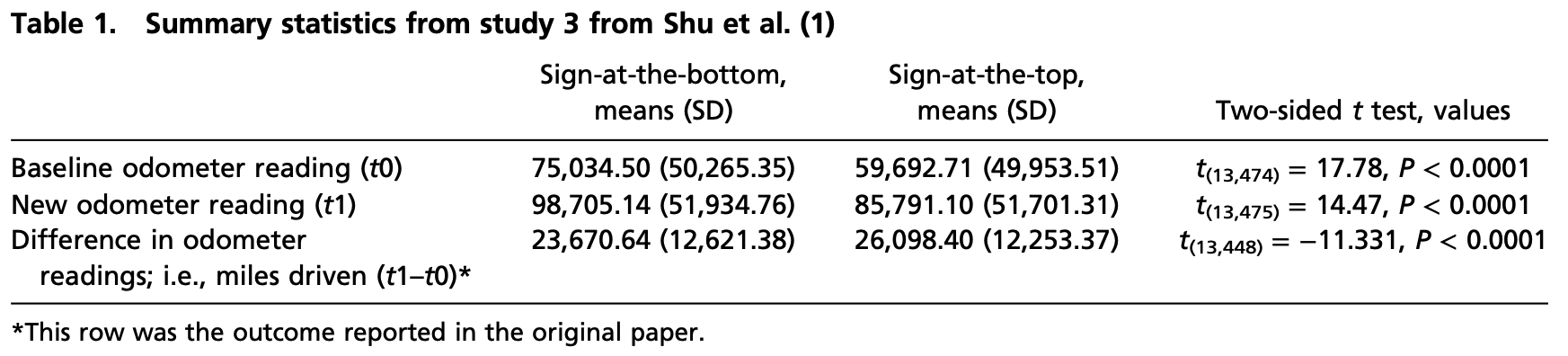

Reproduction of the field trial reported in the 2012 experiment also yielded some interesting results. Summary statistics derived by Kristal and colleagues show that the baseline odometer reading differed materially between the two groups, suggesting a failure of randomisation.

20.1.3 The fraud

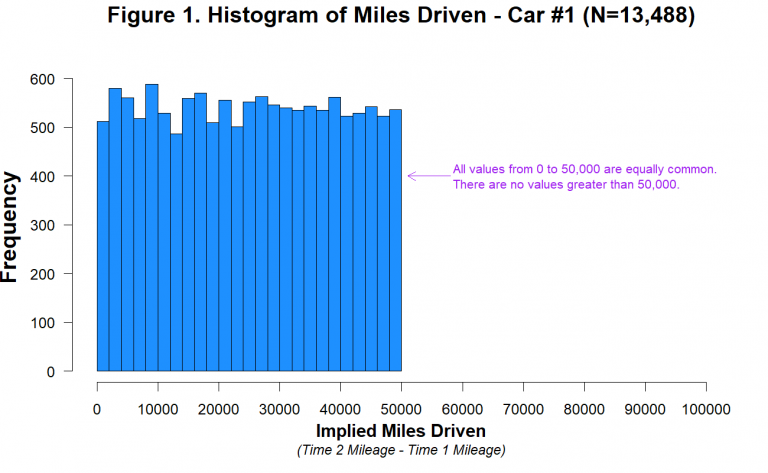

Later analysis by anonymous researchers (Anonymous, 2021) showed that there was not just a failure of randomisation. The field trial data was faked. There were many indicators of this fraud, but one could be seen by simply plotting the reported odometer readings.

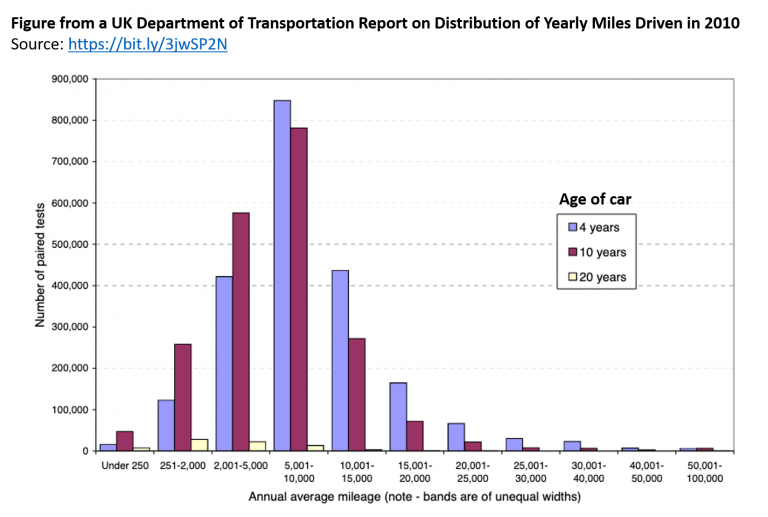

Let’s look at the following two graphs from different papers to show how the distribution in the Shu et al. (2012). should have been (on the left), and how the reported distribution looked (on the right). Someone had randomly generated the data.

If you want to know more, read (Anderson et al., 2016).